|

One of my favorite things about Orton-Gillingham training was the focus on teacher knowledge as the best resource in education. This is something I have come to believe because I have experienced the truth of it. When teaching a graduate course that focused on reading, one of the questions I loved sharing with teachers was, What is the primary ingredient in the recipe for every child’s reading success?

Answer: An effective classroom teacher who has the ability to teach reading to a group of children that have a variety of abilities and needs (e.g., Snow, Griffin, & Burns, 2005; Strickland, Snow, Griffin, Burns, & McNamara, 2002). This means that teachers of reading must understand literacy well enough to

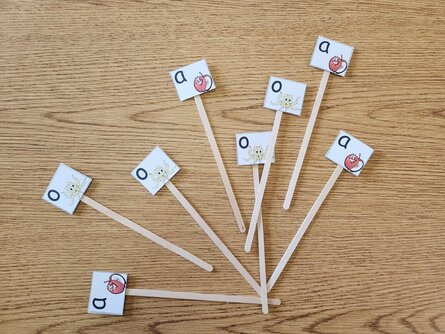

While I am happy that the answer, above, is grounded in research, I also know it to be true from my many years as a learner and educator. We have to understand what students know and can do as well as how they learn and what they most need to learn right now while keeping in mind the greater trajectory of their literacy journeys. Then we have to know how to teach it. This takes time and courage. Time, for example, because many students lack foundational skills past the primary grades, when assessing and teaching them often isn't a priority. Courage, because the results of assessments can feel disappointing to students, teachers, families, and caregivers. They also leave many educators confused about how to proceed given a lack of options around training and coursework that prepares them to meet the many complex needs of students learning to read and write. As I participated in the Orton-Gillingham training, I found so much overlap with the linguistics courses I took when I studying for my English as a Second Language teaching endorsement. It reminded me that many teachers haven't had this specific learning around morphology, syntax, phonetics, and semantics. Those terms sound dry and academic, but they impact every aspect of literacy learning. An example I can give is the a-ha moment some of my learners recently had when they realized they had long been confusing /d/ and /t/ at the ends of words because they didn't realize that one is voiced, and the other is unvoiced. Pointing this out and practicing saying and hearing the sounds helped resolve the issue. Deep knowledge also builds teacher credibility in the eyes of our learners. They want to believe in us, but they have to be shown that we know how to help them be successful. We have to do this over and again because many of them have experienced consistent failure and the negative emotional outcomes that accompany it. There is so much controversy and provocation in the world of teaching literacy. The reading wars have been a hallmark of my entire career, from my pre-service years in the late 1980's until now. It leaves many of us, working by the sides of young people, saddened by what has been lost and wondering what is to be gained by continued contention at the expense of building teacher expertise. What I do know is that there is power in deep knowledge of the reading process and reading instruction. That power, when shared, sets learners securely on the path of a literate future. Comments are closed.

|

Details

AuthorMerten & Morgan Consulting, LLC ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed