|

Did you know that the instructional strategy of Sketchnoting can actually reduce students' stress and enhance focus? In Episode 2 of our 7 part book series on Inks and Ideas by Tanny McGregor, Tanny explains the benefits and research surrounding sketchnoting as an instructional strategy. On page 4, she lists four essential questions that are discussed in Chapter 1. 1. Does sketchnoting align with our beliefs about best practice? 2.What benefits do sketchnotes provide for the thinker/reader/writer/listener/viewer? 3. What does research suggest about the practice of sketchnoting? 4. How important is notetaking, and how does sketchnoting fit in? We discuss Chapter 1 in more detail on our podcast, Academic Conversation with Merten & Morgan. Please listen and leave your comments below! Resources from Episode 2: Guided Comprehension: Visualizing Using the Stretch-to-Sketch Strategy by Sarah Dennis-Shaw on readwritethink.org Proust and the Squid: The Story of Science of the Reading Brain by Maryanne Wolf

0 Comments

Did you know that Frida Kahlo filled the pages of her diary with intense color and emotion or that Bill Gates is a doodler? We are excited to be launching a 7-part series on the latest book by Tanny McGregor, Ink & Ideas: Sketchnotes for Engagement, Comprehension, and Thinking. In our first episode, we discuss the opening chapter of the book. Tanny shares how annotation has always been a part of her life and how people in history have used sketchnoting, specifically as a means to annotate. Over the next 6 weeks, we will be sharing our insights from the book and how sketchnoting impacts students in the classroom. You can listen to Episode 1 of this podcast on iTunes and Soundcloud. Just go to Academic Conversation by Merten and Morgan.

Resource mentioned in Episode 1 How to draw to remember more by Graham Shaw Teachers in school districts across the country are preparing themselves for the end of the school year. This time always brings unique opportunities for celebration and reflection as we think about how to let our students know how much we care about them and how we have enjoyed teaching them and fostering their growth. We remember many things that we hoped we would do that didn’t come to fruition. We look at the faces of our kids and hope that they will remember their time with us as full of opportunities to learn and grow within the safety of a caring and supportive classroom environment. But in addition to all of the things we reflect on, we also start to think about how we can take what we have learned this year, and make next year even better. Because teachers, if nothing else, believe in the concept of continuous improvement based on increased knowledge and experience. How could we do this work otherwise?

One of the first things we can start thinking about as we plan for the upcoming academic year is the layout of the classroom. Schools are full of many different types of rooms that are used to meet with large and small groups of students, and that gives us a wide range of options as we consider how our space can be arranged for optimal learning. Questions that we can use to guide our thinking are, What tools and materials will students need for inquiry, collaboration, and independent application? How can space be used flexibly for larger group lessons? Students need options for grouping configurations and easy access to learning tools including digital ones. How can we plan the layout of the room so that this is not only possible, but encouraged? Related to room configuration is access to learning tools. Learning tools include those resources and materials that students need to direct their own learning choices. Some examples may include paper choice templates, markers, tablets, magnetic letters, math manipulatives, calculators, dry erase boards, graph paper, computers, reference books, and chapter books. Built into student use of learning tools are the procedures and expectations that students will be taught to ensure proper use of materials. One essential but daunting task at the end of the teaching and learning year is packing up the classroom library. As this is done, it’s worthwhile to reflect on how the library can become more responsive to student needs. Which titles were most popular and unpopular with students and why? Are there any student cultural considerations or interests that are missing from the library? How well did checkout and organization systems work? How can titles students don’t check out be replaced with more engaging ones? Where can high-interest low-readability texst be found? A final consideration for looking forward to the next year while finishing the current one is the learning we will need to continue throughout the summer months. We often have good intentions regarding summer planning, but sometimes this is made more difficult simply due to the lack of the professional books we put in boxes and leave in our classrooms. First, are there any outdated or unused books you can donate or recycle? What books do you want to take home with you? Have you considered buying professional books on an e-reader to make them more accessible? Are there books that you know are great, but you want additional time to read in depth? Are there books you can use to plan units with colleagues? Do you have kids’ books in your library that the students love but which you haven’t had time to read? Are there any books your school will be focusing on as a staff next year? These can be placed in a boxed labeled, TAKE HOME! The end of the academic year is a time of many complex and conflicting feelings. We may be seeing students and families leave our buildings that we have known since kindergarten. We may be saying good-bye to cherished colleagues and administrators and welcoming new ones. Some of us will change grades or position. But whatever the case is, thinking about what supported and encouraged student learning and what didn’t, as well as challenging ourselves to direct our attention towards how our rooms will reflect the ways we expect students to engage in learning will benefit us in the year ahead. Mary & Alicia My children love Hayao Miyazaki's movies. I remember when my husband took them to see Howl's Moving Castle when it was released in my hometown. They were hooked. They couldn't stop talking about it. And when I rented (no streaming yet) my first Miyazaki movie, My Neighbor Totoro, I understood the appeal of the world he creates with his unique combination of fantastical story, color, music, and characters. Each of my children has his or her favorites: Tortoro, Sen/Chihiro, Calcifer, Pazu, Nausicaa, Sheeta. So many. My youngest used to sleep with stuffed Soot Sprites tucked in next to him every night. Recently, when I happened to come across a list of Miyazaki's 50 favorite children's books on Open Culture, I was curious and excited. First of all, his 50 FAVORITE children's books? That's a real reader! And I couldn't wait to see what sort of influence books might have had on his imaginative interior life. That is how I came across a book titled, The Ship That Flew by Hilda Lewis.

The Ship That Flew is about the magical adventures of four children who happen upon a model Viking ship that grows to full size when given a command that includes a destination. Upon arrival, it shrinks again to the convenient size of a young boy's pocket. The children fly in the magic ship having adventures in different countries and times. When reading the book, I could easily imagine a young Miyazaki carried away by the gentle tones and colorful fantastic imagery of the story. Everything about this book having a place among Miyazaki's childhood favorites made sense. The thing that truly surprised me about it was the fact that my 14 year old son let me read it to him. Aloud. Did you see that he's 14? He's also my youngest and my child who doesn't remember a world without smart phones, video games, and YouTube videos. He has been the most challenging of my children when it comes to reading books for pleasure, especially fiction. But when I gave him the pitch; all the details of how I found the book and the fact that Amazon labeled it historical fiction for teens (sneaky, I know) he rolled his eyes, but he started listening. And we flew through the pages of the first book we have read together in a long time. Sometimes as parents and teachers, it seems too daunting a task to find a place for real books in the hearts of young people immersed in a digital world. But that place is still there waiting to be found. Those of us who found our childhood favorites must listen, observe, and be their guides. Who know what the next young Miyazaki is waiting to read? I have 49 more tries already lined up for my own son, and endless hope for the young readers who are my students. I have a colleague who reads and recommends books. And that in itself is a treasure. But it also happens that the books she shares with me always bring some aspect of the lives of the students we teach into a bright light of clarity. That light may highlight the humor in situations that make us laugh, it might burn a bright spotlight on an injustice that makes us cry, or it might be the hot light of anger when we recognize a child's face through a character surviving a situation no kid should be made to endure. Jacqueline Woodson's Harbor Me brought all of this and more to this teacher of diverse learners who also considers it a privilege to live in the company of children every day.

The students in Harbor Me are as authentic as they come. These characters reflect the daily dramas that teachers and students are all too familiar with: incarceration, immigration, bullying, learning differences, race, adolescence, and schools as places where the most fragile of young people wait to be seen and heard. They were fortunate to find exactly the teacher they needed in Ms. Laverne. The students and the reader respect this teacher for her subtle masterful ways of building her students' self-esteem and standing back to allow them the opportunity to have real conversations and to become bonded as friends. Every student has a story, and under Ms. Laverne's careful guidance, every story is told to a loving audience when the teller decides she is ready. As I read some of the later chapters of Harbor Me, I became so invested in the story of the main character, Haley, that I had to put the book down, take some deep breaths, and wipe away tears. It takes a brave, honest, and compassionate author to tell the little huge stories of our kids' lives with the respect and elegance that they so deserve. It takes someone who listens with reverence and speaks skillfully. It takes a person who sees no child as an object of pity, and all children as worthy. That is the author who tells of Amari, Haley, Holly, Tiago, Ashton, and Esteban. And I grateful to her for it. Reading Instruction for Diverse Classrooms: Research-Based Culturally Responsive Practice

by McIntyre, Hulan, and Layne Recently, a classroom teacher told me about a class she had looped up with from second to third grade. She described seeing the gap in literacy achievement between her students of color and other students. She knew what instruction they had received. She understood and applied effective strategies. She didn’t know why she couldn’t bridge the gap or even stop it from widening. She felt that she had exhausted her sources of instructional support. She just didn’t know what else to do. That conversation left me thinking about Reading Instruction for Diverse Classrooms. I read it years ago because a colleague, Vicky Layne, is one of the co-authors and I have always admired and respected her work. One of my favorite aspects of this book is that it includes all diverse learners, including culturally and linguistically diverse students. I believe that we can’t address the learning gap until we start to see the common themes represented by the students represented there. And this book does that. Chapter 4 focuses on classroom community and relationships. This is the foundation that culturally responsive instruction, including read and writing, is built on. Specifically, the authors discuss the role of discourse and dialogic instruction. That’s a fancy label for talking to kids using school talk and teaching them to empower themselves to state their ideas and to respond effectively to their peers, teachers, and others. So many of our kids don’t know how to navigate a simple disagreement with a classmate without it spiraling into tears, hurt feelings, or worse. Our kids aren’t given the time or the tools to develop dialogic skills, and sadly, there are few opportunities for them to learn from our modern culture. Addressing this need allows us to build community, relationships, and academic language that feeds reading and writing, yet it is still largely absent from most classrooms. And if you happen to work with English learners, you become acutely aware of the need for oral language models in the classroom and the lack of time set aside for students to interact. One strategy recommended by the authors is Numbered Heads Together (Kagan, 1994). I witnessed the power of this strategy in a fifth-grade classroom this year. Students who were disengaged suddenly cared a lot about their response to a question posed by the teacher when the element of chance was introduced to the selection of the group speaker. Students who felt they were misrepresented by their speaker had to reconvene to decide how they could improve their listening skills. Others clapped spontaneously when a shy or low language student, given the benefit of oral rehearsal and group cooperation wowed the class with a thoughtful response. That one strategy changed the whole dynamic in the classroom. And Reading Instruction for Diverse Classrooms includes additional strategies for building dialogic skills and classroom discourse, grounding research, and an index where more can be learned. I highly recommend this book to any instructor teaching students how to read, write, listen, and speak in today's classroom. I say today's classroom because today's classroom is diverse. I hope we all remember that, “Reading and writing float on a sea of talk” (Britton, 1970) and that we are empowered to lift the literacy lives of kids by using dialogic instruction. More to come soon with a special surprise in our next podcast! Mary I was teaching a self-contained 4th/5th class in an urban school when I realized I needed to understand how to teach reading. Really teach it. From the beginning. The students who made that very clear to me were my newcomer English learners (ELs). ELs come from all language and literacy backgrounds. Some are literate in another language, some come from cultures where generations of people have not had the opportunity to learn to read and write. But they all had in common that they needed to start with reading foundations and I didn't know how or where to begin.

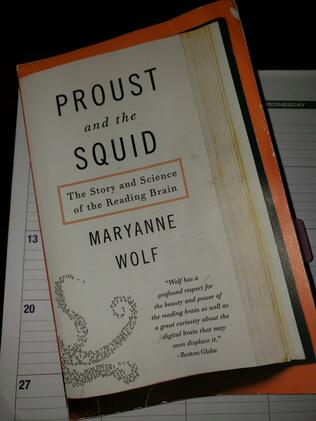

My students inspired me to start my journey as a literacy teacher. One who teaches students who are expected to read to learn while they are learning how to read. This is a daunting task. There are no easy answers, but there are many researchers and experts whose work has been pivotal in my development as a teacher. One of these, whose book I recently read is Maryanne Wolf. Her book is titled Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. This book was published in 2007, and the fact that I didn't learn about or read it until 2018 says a lot about what prevents our students from becoming fluent at listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Wolf writes in beautiful scientific prose about what has had to happen over time for our brains to be able to read. One of my favorite quotes is this: Each brain of each ancestral reader had to learn to connect multiple regions in order to read symbolic characters. Each child today must do the same. Despite the fact that it took our ancestors about 2,000 years to develop an alphabetic code, children are regularly expected to crack this code in about 2,000 days, or they will run afoul of the whole educational structure--. (p. 222) This book really brought into focus the work of the reading brain. This is the science that teachers want and need, but to whom, for some reason, it is denied. We aren't hard-wired to read as we are to speak. The understanding of the brain-science, married with expertise in reading and writing approaches and strategies that build fluency in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, oral language, and writing will give teacher the agency to make decisions on learners based on effective assessments and sound pedagogy. Our kids deserve this. We know it. As one of my graduate students put it, "Teachers need the WHY behind the HOW. I can recognize a strategy that seems to be useful. But when I know WHY it works, then I step out of the fog and into the light!" Let's bring our kids into the light of literacy...we can't wait! Mary  Children of all ages love to create. How many times have you seen a child draw or doodle on a napkin or on a piece of paper waiting for food at a restaurant or just to pass the time? Children are natural writers. They scribble, doodle, and even add dialogue at times. When children write, the process of reading is reinforced. Children have to use so many literacy skills to write. They use what they know about phonics, writing conventions, brainstorming, editing, and reading. Children have to think and to remember the message they want to compose and reread it several times to convey what they are trying to say. They are naturally discerning about subject matter and word choice. Getting a child to write can be daunting and frustrating for the adult and the child. A fun, authentic, and engaging way to get children to write is through book making. This can be done in the classroom and at home. I was reminded of this process over winter break after reading a book called A Teacher's Guide to Getting Started With Beginning Writers by Katie Wood Ray and Lisa Cleaveland. The book discusses the first 5 days of school and how to jump right into book making with children. By simply stapling some paper together and letting children create, children are writing and reading from day one. What an ingenious way to assess students, have an authentic task on the first day of school that any child can accomplish, while creating a sense of classroom community. Most children like to talk and share about what they are creating. Can you imagine the book collection children will have at the end of one school year. How many hours of literacy practice they would have, just by an hour a day of making and sharing books. Just as many practices that are taught in school are transferred to the home, when students are truly engaged, many students will be asking for paper and a stapler at home. Get ready to create!

|

Details

AuthorArchives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed