|

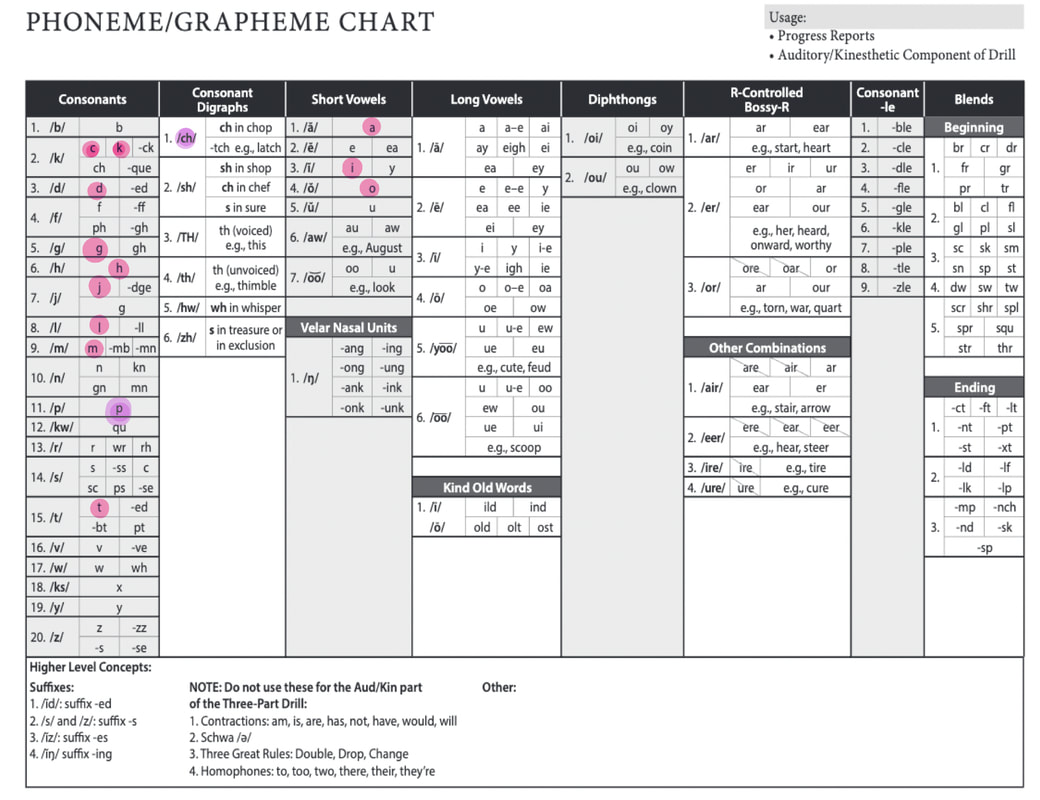

Much has been written and said about the importance of the relationship between learners and their instructors. Positive relationships are believed to positively affect academic engagement, attendance, grades, and behavior (Sparks, 2019). The shared beliefs about this topic can be found across many digital and non-digital platforms including everything from, "Relationships before rigor," to "Students don't care how much you know until they know how much you care," and "My students don't need me to learn. They need me to care." What we find in our work with literacy learners, is that students do want their teachers to care about them. Of course they do. They greatly benefit from a curious, empathetic instructor with excellent communication skills, especially when it comes to listening to understand. Curiousity extends to cultural background as well as family life and learner preferences and interests. However; what we have found, is that the thing learners most want from their teachers is confidence in that person's instructional credibility. In other words, they want to feel confident that their teacher knows the subject(s) being taught deeply and can help the students improve. To be academically successful. Especially if that student perceives that they are behind expectations of their current grade. Doug LeMov (2019) calls this connecting through content and describes it this way, "A teacher who would place more value on showing caring without ensuring learning would have done you a disservice. It would have been an act of egotism. And you would have come to resent that." Similarly, Cornelius Minor (2018) wrote simply, "To be a radical teacher, you must be a master at teaching your content." What this means to us, is further validation of the fact that the most important factor for student learning is a teacher with deep knowledge (Hammond, 1999). We know this because we have lived and learned alongside students for the past quarter-century. We pay attention to what helps student become confident and successful. When we don't get the results our clients deserve, we take time to deepen and widen our knowledge and skills as instructors. So far, we have yet to find students who don't respond to a research-based teaching method that we have learned. Often it is a combination of approaches that work. Always, we develop and engage in learning experiences with empathy and curiousity about the learner, but also with the responsiveness that only comes from deep knowledge. If you are curious, empathetic, desiring of learning more about the teaching and learning of literacy, reach out to us. We love to talk with teachers, parents, caregivers, policy-makers, professors, reallly anyone with a passion for literacy learners! As always, you can leave a comment below or send a comment on Facebook or Twitter. We are here and we would love to hear from you! Lemov, D. (2018, September 17). Connecting through content, teach like a Champion. Teach Like a Champion. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://teachlikeachampion.org/blog/connecting- through-content/ Minor, C., & Alexander, K. (2020). We got this: Equity, access, and the quest to be who our students need us to be. Heinemann.  Image by vectorjuice on Freepik We work with literacy learners. While we understand that it can be disorienting for families and caregivers to learn explicitly about the needs of their learners for the first time after long periods of expressed concern, we would argue that it's even more difficult for the students themselves. The impact of academic difficulty is greatest on them and often results in feelings of helplessness, frustration and anger when they learn that this information has not been openly communicated with them. No matter the reason. We believe that the solution can be found through effective assessment, clear communication of results to families and students, deep instructor knowledge that allows responsiveness to the needs of each learner, and progress monitoring that has a clear connection to literacy goals. When we assess students, we use research-based diagnostic assessments of specific skills or components of reading. We communicate those results. We also create a plan for building on student strengths to support new learning. It's essential for students to be involved in this process as they are often aware of where their difficulties lie and are eager to learn what they can do about it. One example of a progress monitoring tool that empowers students as ongoing learners is a phoneme-grapheme chart that can be filled in as students master phonics concepts. They can see their progress and are motivated to work toward a goal that has become more concrete. Another example is student writing. When a rubric is clearly shared and students apply it regularly, they can begin to see for themselves how much their writing is improving over time. Students are very aware of their own strengths and needs and how those affect their learning. They also know which instructors can help them move forward. John Hattie (2008) calls this teacher credibilty, meaning that students do perceive which adults can make a difference in their learning, and if they don't believe that an instructor is credible, they "just shut down." We have spent long careers building our understanding of how to assess and teach literacy learners. We have many concrete examples of how our approach has changed student attitudes toward reading, writing, and even their own efficacy as learners. This is why we continue to do what we do, and we would love to tell you more! Contact us here, on our Facebook page, or at [email protected] to start the conversation. References Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning. Routledge. |

Details

AuthorMerten & Morgan Consulting, LLC ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed