|

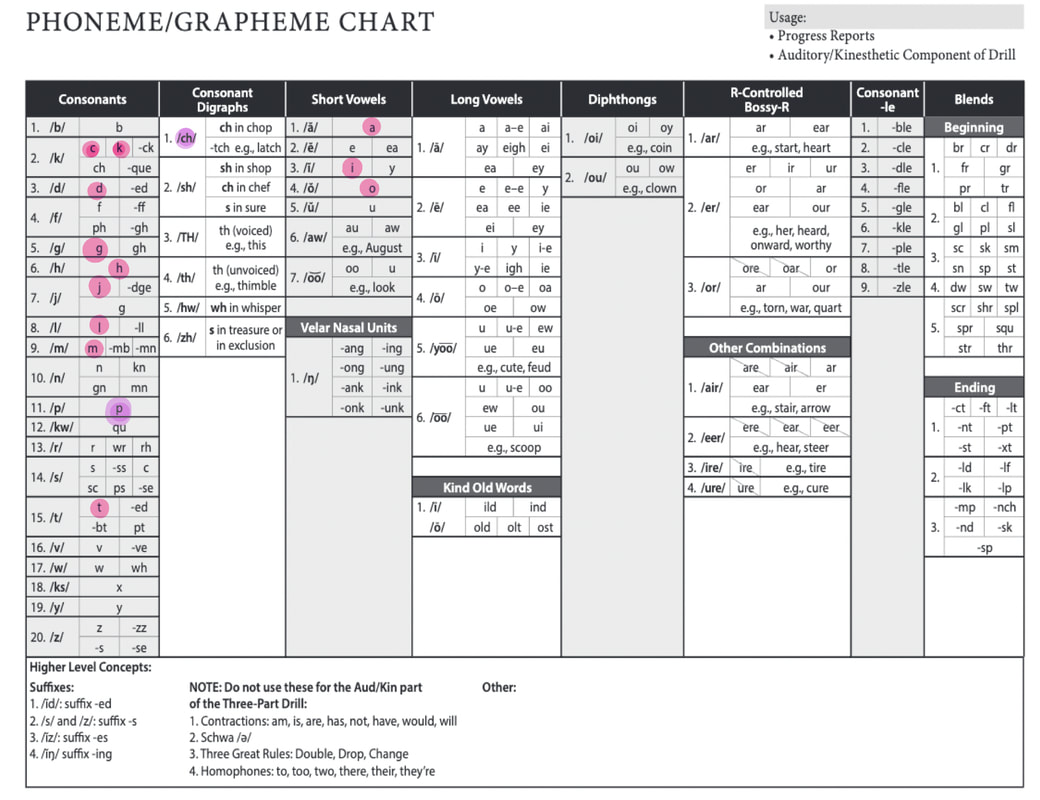

Much has been written and said about the importance of the relationship between learners and their instructors. Positive relationships are believed to positively affect academic engagement, attendance, grades, and behavior (Sparks, 2019). The shared beliefs about this topic can be found across many digital and non-digital platforms including everything from, "Relationships before rigor," to "Students don't care how much you know until they know how much you care," and "My students don't need me to learn. They need me to care." What we find in our work with literacy learners, is that students do want their teachers to care about them. Of course they do. They greatly benefit from a curious, empathetic instructor with excellent communication skills, especially when it comes to listening to understand. Curiousity extends to cultural background as well as family life and learner preferences and interests. However; what we have found, is that the thing learners most want from their teachers is confidence in that person's instructional credibility. In other words, they want to feel confident that their teacher knows the subject(s) being taught deeply and can help the students improve. To be academically successful. Especially if that student perceives that they are behind expectations of their current grade. Doug LeMov (2019) calls this connecting through content and describes it this way, "A teacher who would place more value on showing caring without ensuring learning would have done you a disservice. It would have been an act of egotism. And you would have come to resent that." Similarly, Cornelius Minor (2018) wrote simply, "To be a radical teacher, you must be a master at teaching your content." What this means to us, is further validation of the fact that the most important factor for student learning is a teacher with deep knowledge (Hammond, 1999). We know this because we have lived and learned alongside students for the past quarter-century. We pay attention to what helps student become confident and successful. When we don't get the results our clients deserve, we take time to deepen and widen our knowledge and skills as instructors. So far, we have yet to find students who don't respond to a research-based teaching method that we have learned. Often it is a combination of approaches that work. Always, we develop and engage in learning experiences with empathy and curiousity about the learner, but also with the responsiveness that only comes from deep knowledge. If you are curious, empathetic, desiring of learning more about the teaching and learning of literacy, reach out to us. We love to talk with teachers, parents, caregivers, policy-makers, professors, reallly anyone with a passion for literacy learners! As always, you can leave a comment below or send a comment on Facebook or Twitter. We are here and we would love to hear from you! Lemov, D. (2018, September 17). Connecting through content, teach like a Champion. Teach Like a Champion. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://teachlikeachampion.org/blog/connecting- through-content/ Minor, C., & Alexander, K. (2020). We got this: Equity, access, and the quest to be who our students need us to be. Heinemann.  Image by vectorjuice on Freepik We work with literacy learners. While we understand that it can be disorienting for families and caregivers to learn explicitly about the needs of their learners for the first time after long periods of expressed concern, we would argue that it's even more difficult for the students themselves. The impact of academic difficulty is greatest on them and often results in feelings of helplessness, frustration and anger when they learn that this information has not been openly communicated with them. No matter the reason. We believe that the solution can be found through effective assessment, clear communication of results to families and students, deep instructor knowledge that allows responsiveness to the needs of each learner, and progress monitoring that has a clear connection to literacy goals. When we assess students, we use research-based diagnostic assessments of specific skills or components of reading. We communicate those results. We also create a plan for building on student strengths to support new learning. It's essential for students to be involved in this process as they are often aware of where their difficulties lie and are eager to learn what they can do about it. One example of a progress monitoring tool that empowers students as ongoing learners is a phoneme-grapheme chart that can be filled in as students master phonics concepts. They can see their progress and are motivated to work toward a goal that has become more concrete. Another example is student writing. When a rubric is clearly shared and students apply it regularly, they can begin to see for themselves how much their writing is improving over time. Students are very aware of their own strengths and needs and how those affect their learning. They also know which instructors can help them move forward. John Hattie (2008) calls this teacher credibilty, meaning that students do perceive which adults can make a difference in their learning, and if they don't believe that an instructor is credible, they "just shut down." We have spent long careers building our understanding of how to assess and teach literacy learners. We have many concrete examples of how our approach has changed student attitudes toward reading, writing, and even their own efficacy as learners. This is why we continue to do what we do, and we would love to tell you more! Contact us here, on our Facebook page, or at [email protected] to start the conversation. References Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning. Routledge. I just finished listening to Emily Hanford's podcast series, Sold a Story. In it, she discusses current reading teaching methods, Science of Reading, and popular authors and publishers of reading and writing curricula. It's fascinating, to say the least. Much of it rang true to me because I have lived it through my work as an educator, a teacher-trainer, an adjunct, a Literacy Specialist, and a small business owner focusing on literacy. The point that sticks with me from the final podcast in the series is the number of teachers who started questioning their teaching methods because they had a child or children of their own who struggled to learn to read. Why is this, when so many kids in classrooms across the country also struggle to read?

Over the years, I have heard numerous comments from some colleagues indicating that students aren't successful in intervention because of factors inherent in the student or the student's home. Some examples include ability to focus, language spoken at home, home practice of skills, and motivation. The subtext here is that the student must fit the intervention instead of the intervention meeting the needs of the student. I don't think that the educators I know have purposely set out to place obstacles in the path of a student's literacy learning. Teachers want students to succeed; but when the training and materials available only work sometimes, they feel desperate to understand why. They are also told that they need to figure this out because they are responsible for student outcomes regardless of the research available on the efficacy of the methods they are expected to use. This is why, at Merten & Morgan, we have continued to learn and expand our knowledge of the reading process which includes current research on the brain and how it learns to read and write. We have a wide array of tools we can use with kids based on what is needed. This includes writing and comprehension instruction which motivates learners to read and write more. Instead of blaming the child, we support the child because we know the child through specialized assessments and effective instruction. We hope that soon the conversation about reading will lead to support and successful literacy learning for more kids. If you want to know more about what we do for families, students, and educators, reach out in the comments below, on our facebook page, or at [email protected]. We would love to hear from you. One of my favorite things about Orton-Gillingham training was the focus on teacher knowledge as the best resource in education. This is something I have come to believe because I have experienced the truth of it. When teaching a graduate course that focused on reading, one of the questions I loved sharing with teachers was, What is the primary ingredient in the recipe for every child’s reading success?

Answer: An effective classroom teacher who has the ability to teach reading to a group of children that have a variety of abilities and needs (e.g., Snow, Griffin, & Burns, 2005; Strickland, Snow, Griffin, Burns, & McNamara, 2002). This means that teachers of reading must understand literacy well enough to

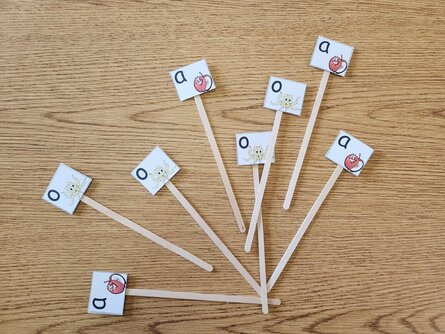

While I am happy that the answer, above, is grounded in research, I also know it to be true from my many years as a learner and educator. We have to understand what students know and can do as well as how they learn and what they most need to learn right now while keeping in mind the greater trajectory of their literacy journeys. Then we have to know how to teach it. This takes time and courage. Time, for example, because many students lack foundational skills past the primary grades, when assessing and teaching them often isn't a priority. Courage, because the results of assessments can feel disappointing to students, teachers, families, and caregivers. They also leave many educators confused about how to proceed given a lack of options around training and coursework that prepares them to meet the many complex needs of students learning to read and write. As I participated in the Orton-Gillingham training, I found so much overlap with the linguistics courses I took when I studying for my English as a Second Language teaching endorsement. It reminded me that many teachers haven't had this specific learning around morphology, syntax, phonetics, and semantics. Those terms sound dry and academic, but they impact every aspect of literacy learning. An example I can give is the a-ha moment some of my learners recently had when they realized they had long been confusing /d/ and /t/ at the ends of words because they didn't realize that one is voiced, and the other is unvoiced. Pointing this out and practicing saying and hearing the sounds helped resolve the issue. Deep knowledge also builds teacher credibility in the eyes of our learners. They want to believe in us, but they have to be shown that we know how to help them be successful. We have to do this over and again because many of them have experienced consistent failure and the negative emotional outcomes that accompany it. There is so much controversy and provocation in the world of teaching literacy. The reading wars have been a hallmark of my entire career, from my pre-service years in the late 1980's until now. It leaves many of us, working by the sides of young people, saddened by what has been lost and wondering what is to be gained by continued contention at the expense of building teacher expertise. What I do know is that there is power in deep knowledge of the reading process and reading instruction. That power, when shared, sets learners securely on the path of a literate future. Recently, we completed Orton-Gillingham Comprehensive Plus training offered by the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (IMSE). There are many reasons for this, including the patterns we have seen emerge among the many literacy learners we assess and instruct: lack of phonics knowledge, lack of fluency with reading and writing high-frequency words, difficulty with and aversion to writing, and a deep desire to read at the level needed to fully participate in the classroom. As usual, learners are our guides to gaining the tools we need to instruct them better.

In the past, we created a Reading Toolkit for one of our partners, The Sandra Dunagan Deal Center for Language and Learning in Georgia. Through that process, we learned a great deal about multi-sensory instruction and became curious about how it could be most effectively used with our learners. We also picked up a text titled Proust and the Squid by Maryanne Wolf and read it together. Our thinking continued to shift and expand. We learned about appropriate use of decodable books from a professional development session by Pam Kastner. Soon thereafter, I read a recommendation from a Literacy Specialist regarding the use of word sorts, such as Words Their Way, and Orton-Gillingham. I had already noticed that some of my learners needed modified sorts and some really struggled to understand them. A scope and sequence from Recipe for Reading by Nina Traub was cited and that set me on the path of learning how I could use this to make my word sort instruction more effective. This led to a commitment to 30 hours of Orton-Gillingham training. Learning how to teach reading and writing (listening and speaking, too) is a life-long journey. There are many opportunities to reflect on what is and isn't benefitting students and to try to understand the reasons why. We have both sought as much professional development and coursework possible to expand our scope of practice. That has lead us to the National Board Certification process, to Literacy Specialist Certification and to many conferences, books, articles, and peers who we believed could help us help students. Now we have added Orton-Gillingham instruction to our toolboxes and we have immediately seen positive results with many students. This is happening at a time when Science of Reading is getting a lot of attention, especially where we live and work, and it is helping us form and reform our beliefs and understandings about how students learn to read. If you would like to know more about this topic, or others related to literacy, take a look a our podcast page. Our podcast is titled Academic Conversation with Merten & Morgan and in it we discuss our literacy journey, including a series about Proust and the Squid. You can also reach out in the comments, on Facebook, or using our gmail: [email protected]. We love to learn alongside teachers, families, caregivers, and others who want to build a literate future for all students. |

Details

AuthorMerten & Morgan Consulting, LLC ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed